Librarians-in-Residence: Publications

INTO THE TORNADO – NOTES FROM THE HARDCORE ART BOOK FAIR IN MEXICO CITY

Michael Guo from te editions

A TERRIBLY TIMED VISIT

Arriving in La Condesa, Mexico City, I found myself struck by its uncanny resemblance to Shanghai’s former French Concession. I suddenly understood why the organisers had directed us to this particular neighbourhood, since this was our first time being invited to Mexico City as a book fair exhibitor. The street level of our hotel housed a bar and Italian pizzeria operating in perpetual motion, from dawn to midnight, infusing the district with convivial energy. I observed many expatriates who had acclimatised themselves to this tropical land, walking their dogs through parks and jogging with practised ease. Residents of La Condesa had all seemed to master English with impressive fluency. Boutique cafes and brunch spots decorated every block. My senses strained to absorb this urban abundance. So, here I was, the effervescent and vital Mexico that everyone imagines. My instinctive foreigner’s caution and incompatibility evaporated upon arrival, soon superseded by an inexplicable realisation – I didn’t choose these sights. They were equally imposed on every tourist, much like a hotel television’s automated welcome message. That weekend, an anti-gentrification movement rolled out in the neighbourhood. We did not witness it directly, but the algorithm immediately delivered curated short video feeds about Mexico based on my coordinates collected by location services. The first video showed up on my news feed: American citizens swore they’d never move back home, given Mexico’s superior lifestyle at significantly cheaper cost. Then, the second video followed: a shop located in the Roma District (another gentrified neighbourhood) was completely robbed, with its windows smashed to pieces and inventory ransacked. Walking the streets, we saw a message written on a wall: Your Airbnb was my neighbourhood. And here we were. That was our mode of ‘intrusion’ into Mexico City.

Your Airbnb Was My neighbourhood, photographed in the Roma district, Mexico City. Image courtesy of te editions

A LAKESIDE BOOK FAIR

Mexico City is home to the world’s largest museum of anthropology, and coming here from a neighbouring country, our visit carries, in some sense, a slight anthropological perspective.

Ever since I moved to the United States, the term ‘US-Mexico border’ and stories around that wall have kept appearing in the news. Although Mexican communities are ubiquitous across the United States’ geography, they remain the ‘other’ in the American mainstream narrative. But what do we see when Mexico asserts itself as the subject of a narrative? As tourists, we were aware that our freedom and ease here were luxuries, afforded by cheap prices, delectable cuisine, and an extensive list of art exhibitions we could not possibly exhaust. Under sunlight, people strolled leisurely through neighbourhoods suffused with lush vegetation; their evenings were spent indulging in the alluring aroma of Mezcal. A Mexican friend astutely encapsulated the essence of our experience: La Condesa represented a mere 5% of what Mexico truly was. Indeed, life in La Condesa was worlds apart from the daily routines of most Mexican people. A more pervasive reality was exemplified by what we encountered on our journey from the airport: exhaust fumes permeating every corner of the street, the uneven, meandering road surface we traversed, and the megaphoned hawking of fridge and laundry machine recyclers. Amidst all this, one thing kept us grounded, something we could hold onto – the portraits of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera featured on a 500 peso note. Art is something that can be held in our palms, circulated, and passed down by hands.

Lolo Press, an art magazine stand in Mexico City. Image courtesy of te editions

Our work as te editions often allows us to gain insights into a city and its country through book fairs. These venues serve as a meeting point for creators in the fields of art and design, as well as for leftist intellectuals and independent publishers. While saying this risked oversimplifying a much more complex cultural landscape, the issues, concerns, and discussions raised among creators and independent publishers in Mexico offered us, to some extent, glimpses into shared social reality. In the book Tropical Reading: Photobook and Self-Publishing, editor Liu Chao-tze observes that artbook fairs are not exclusive to free societies.[1] I would add that they are not exclusive to ‘developed countries’ either. Regions undergoing development are often subjected to more complicated issues and dynamics, making the fact that people continue to create despite limited resources a testament to the very spirit embodied by artbook fairs. For distant exhibitors like ourselves, fairs become rare portals into local communities, compressed into brief temporal windows. Can Can Press, one of the artbook fair’s organisers, simultaneously operates as a design studio. This duality oriented the fair toward visual primacy. Text-based publications were scarce, and any literature was predominantly in Spanish. This made our exploration considerably more difficult, but it also illuminated a deeper truth to us: ‘legibility’ extends beyond language into cultural realms, demanding time and patience to cultivate.

The fair occupied an urban park exceeding New York City’s Central Park in scale. At its heart, there was a vast lake. Whilst the fair took place over the long weekend, city dwellers engaged in various sporting activities around the lake, such as water games, walking, and boating. Museums also surrounded the fair’s vicinity, including one housing Diego Rivera’s famous underwater mural El agua, origen de la vida in its collection. Perhaps blessed by this aquatic deity, our Mexican exploration began with water.

Lago Algo, venue of the book fair. Image courtesy of te editions

THE PACIFIC CURRENTS AS MEASURING SCALE

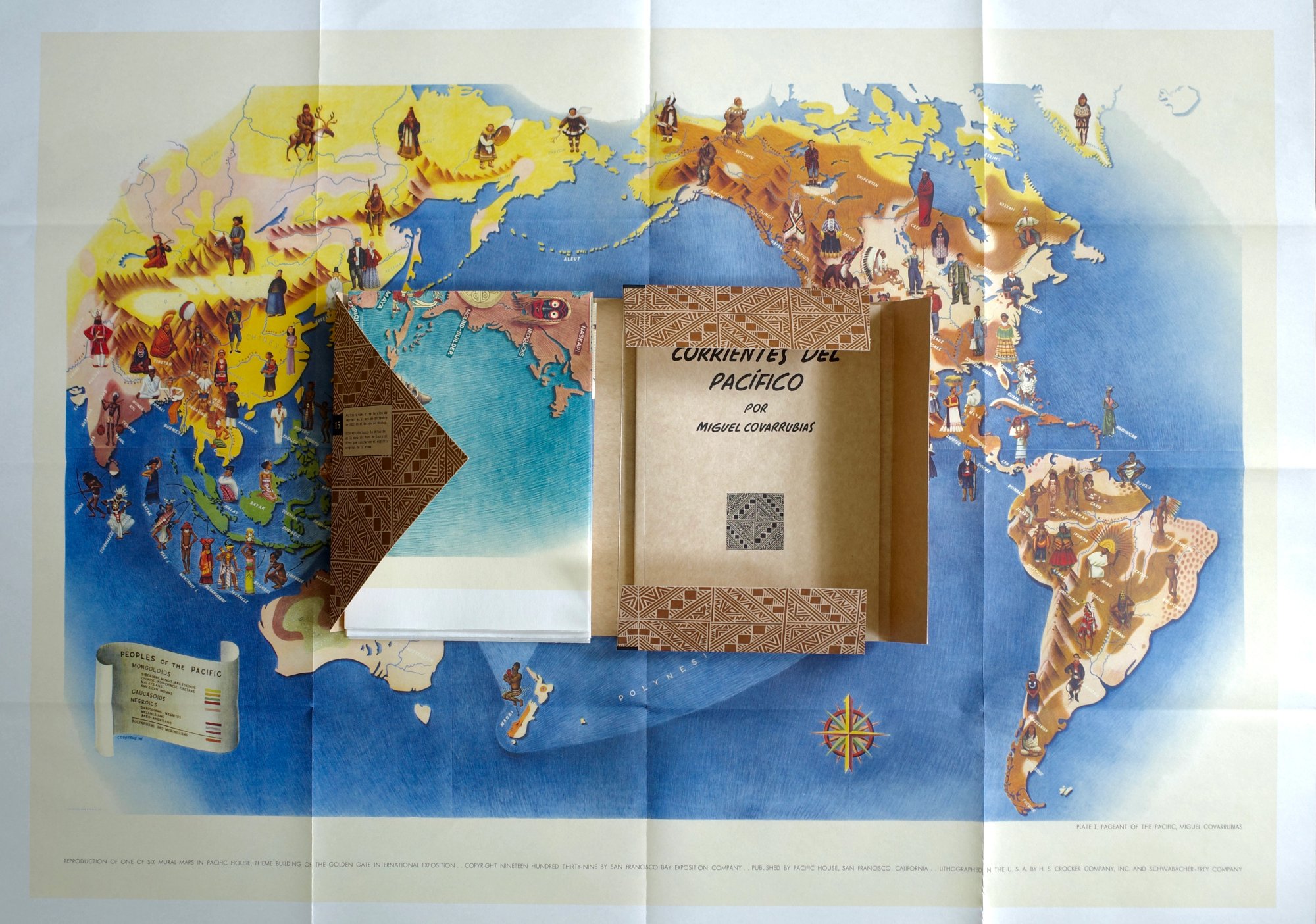

My introduction began with Alias, the Spanish publishing house founded by artist Damián Ortega. Its catalogue, with a direct emphasis on social and artistic practice in Latin America, provided a key channel for me to understand Mexico. Alias’s members recommended Corrientes del Pacífico, a book by Miguel Covarrubias, to me. Though it had a simple cover, closer reading revealed its abundant content, which belied its plain exterior. Covarrubias took on multiple identities – a caricaturist for a number of media outlets, collector, anthropologist, and set designer. As a principal illustrator for the Vanity Fair, he rose to prominence in New York City’s glittering fashion scene; beyond his day job, he dedicated himself to long-term ethnological investigation in Asia and Latin America. His influence was felt even in the East, where his 1930s visit to Shanghai left a direct imprint on Chinese artists such as Zhang Guangyu and Ye Qianyu.

Zhang Guangyu reminisced about his first meeting with Covarrubias: ‘The arrival of Mexican artist Covarrubias brought with him a sense of tropical cloud spectacles hovering over Bali, that Island of Poems. How inspired I felt, as if I had almost ascended and become an immortal.’[2] Reading this, I recalled the shape-shifting sequence from my childhood animation Havoc in Heaven, when Sun Wukong and Erlang Shen locked in a metamorphic duel. Could Covarrubias’s artistic vision have magically touched even these transformations?

‘Peking Opera Singer’ by Miguel Covarrubias, 1933. Collection of Zhang Guangyu Art Foundation. Image courtesy of te editions

Back to the cartographic anthology itself. It originally began as a series of murals Covarrubias painted as a commission for the San Francisco Pacific House at the Golden Gate International Exposition. Titled Pageant of the Pacific, the murals were a set of thematic maps depicting specific elements of the Pacific Rim: its people, animals and plants, economy, housing, transportation, art, and others. Grounded in Covarrubias’ ethnological research, these images gushed with bold colours and an intense life force, so candid and unreserved that I wished I had seen them much, much earlier. Notably, the Pacific and its surrounding worlds occupied the visual centre of these murals, while Europe was virtually absent. At a time when mapping was considered a tool for consolidating territories and sovereignty, these murals undoubtedly offered an alternative imagination for interpreting the human-nature relation. For me, they served as a direct and unembellished evocation of the historical connection between Mexico and Asia, two parts of the world facing each other across the Pacific waters. The relevance of this connection is evident today, as young generations in contemporary Mexico are enthusiastic about K-pop and Japanese manga. Many also choose to study abroad in China. During the fair, we met five or six Mexicans who spoke Chinese, and to our surprise, we even saw two strangers conversing in Chinese right in front of our booth.

As early as nearly a century ago, people had already begun to gauge a new cultural possibility, one not reliant on a Western-centric world structure. The Pacific Rim then, just as now, was a region ripe with bright prospects.

Pacific Currents, by Miguel Covarrubias, published by Alias Editorial, 2022. Image courtesy of te editions

AFFLICTION IS A PRESUPPOSITION

Hydra – we knew of this platform before arriving in Mexico City, a hybrid space functioning as a publisher, bookshop, and art gallery. Its name invokes a monster with multiple serpentine heads from Greek mythology: if you chop off one head, it regenerates two. ‘This is exactly how independent publishing works,’ explained Anna, Hydra’s director. It dawned on me that the recent predicaments associated with independent publishing were in fact shared global concerns. Yet, by choosing this name at inception, these creators anticipated a reality where inevitable struggles were bound to happen. This notion felt like an underlying logic for all of Mexico, hidden beneath its seemingly colourful appearance.

The philosophy behind the name also extends to the content Hydra produces. Many of the books featured at the fair originated from their ongoing workshop incubator projects, and their authors are often amateur artists. One of the publications, Ángel Miguel, took the artist Isabel Moreno Cortez five years to finish, as a project born from the doubled trauma of losing her unborn son Ángel and her older brother Miguel who committed suicide more than two decades ago. The book not only bears witness to the passing of two family members, it also spotlights a linguistic void: there is not a word in the entire world to denote a ‘mother who has lost her child.’ Two volumes are tied via a rope of twisted thread resembling an umbilical cord, entwining the author’s loss of a child with that once endured by her mother. As the artist reflected, ‘How many hearts that never beat once remain untold in each family? How many silenced deaths? How many mournings eluded our sight?’ It makes you wonder how much courage it takes to approach such a heavy topic. At the same time, this book gives form to her afflictions, becoming a means to sort her sorrow, write down memory, and rebuild herself. Absence, another artist book which nearly went out of print, weaves together the narratives of three women through poetic texts and images. It chronicles their fight to survive under the menacing shadow of ‘absence’, pointing to core issues for Mexico and the rest of the world: abduction, murder, immigration, domestic violence – and the invisible gaps where judicial, social, and political systems have collectively failed. Absence is composed of three independent yet interconnected volumes, braided into a unity by a unique bookbinding design. It’s a powerful metaphor that elevates individual destinies while highlighting their commonality, like a whisper, recounting wounds too painful to put into words.

Ana Casas Broda, founder of Hydra Bookstore. Image courtesy of te editions

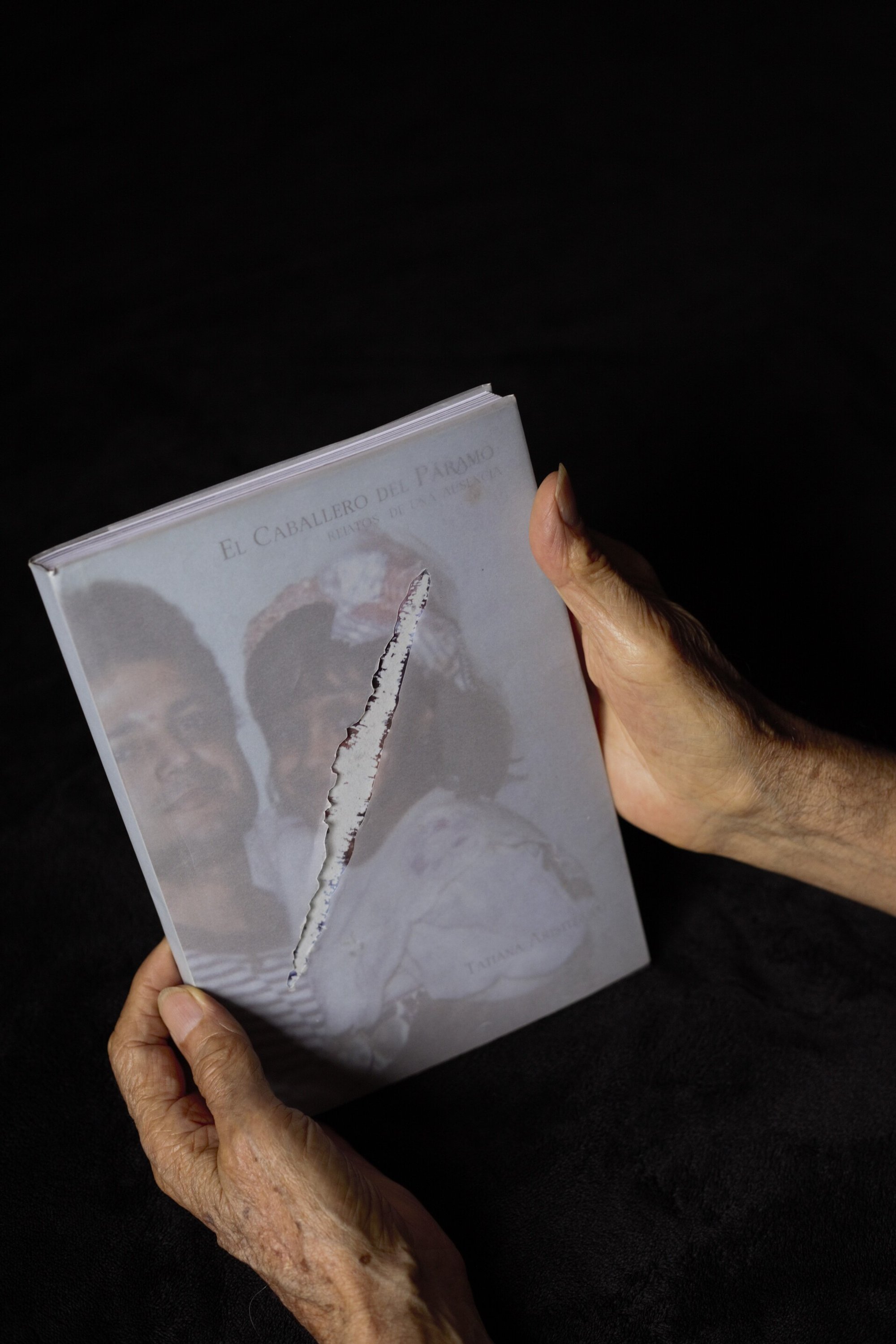

Raya Editorial, an imprint from Colombia, engages with similar subjects. A primary portion of their publishing output centres on the remnants of and reverberations from the Colombian Civil War. Raya’s director, Santiago, takes a hands-on approach to each book’s design, endowing them with the qualities of an art piece. The experience of flipping through and perusing the pages goes beyond the act of reading. This is exemplified by a photobook, Disparos x Disparos, a brainchild of Raya and artist Alexa Rochi. The book documents the photojournalistic journey of the artist following Colombian anarchist female guerrillas. Its cover applies metal materials and a green bandana that readers must untie before opening the book. The act of removing the bandana is akin to revealing secrets from the depths of a jungle. More striking still is another book, El caballero del páramo, which left an even deeper impression. It centres on the memory and reconstruction of the abduction of the author’s older brother. Topographical videos captured by the author from the abduction site are accompanied by precious photos and letters her mother wrote while searching for her child. These archival fragments reproduced from a life surrounding a real abduction are organically interlaced into a multi-vocal narrative of being missing, searching, and memory. The most profoundly touching part is its tactile cover: a deeply incised ‘scar’ stretching across the entire surface, creating a visceral, prickly discomfort beneath the fingers.

El Caballero del Páramo (The Knight of the Moorland). Image courtesy of Tatiana Aristizábal.

We made a deliberate choice to hold a sharing session in Mexico for our new book, Minnan Exit, published in 2024. Created by artist Wen-You Cai, this book is a documentation of videos she took of her family funerals over seven years, intricately expounding and reflecting on notions of decease, funeral rituals, and the philosophy of life and death in Minnan culture. It was surprising to see a book about a local culture from Southern China resonate so deeply in Mexico, across such a vast geographical distance. This resonance, I realised, must stem from a shared imagination of death in our respective cultures. Death in Minnan is less a final termination of life than a ritualistic existence to retain connection with ancestors; similarly, in Mexico, funerals are vibrant festivals – the most quintessential example being Día de los Muertos. This day is not only for mourning past family members, but also for drinking and gathering with the deceased. It was precisely for this reason that the word ‘muerto’ (death) appeared on so many book covers at the fair – certainly not a deliberate gesture of eccentricity but a routine cultural expression. Behind this routine lies Mexico’s complex and persistent social reality, a country that constantly oscillates between disturbance and turmoil. Issues like illegal substances, violence, systematic corruption, economic inequality, the marginalisation of indigenous people and many more tear at the social fabric, leaving it in immense rifts. Within this environment, people have adapted to living with afflictions and in parallel to death. Death is no longer a taboo, but a presence one must face. This cultural atmosphere becomes the naturally fertile soil and context from which the publications at the fair emerged. As the Mexican poet Octavio Paz wrote, ‘The Mexican is familiar with death, jokes about it, caresses it, sleeps with it, celebrates it.’ (1950)

Emerging Mexican publisher No Estamos Muertos (We Are Not Dead). Image courtesy of te editions

Minnan Exit book talk at the Hardcore Art Book Fair. Image courtesy of te editions

THE OTHER SIDE OF DISAPPEARANCE AND DEATH LIES REBIRTH

An inattentive glance might have missed Bebëditora, a ‘small publishing house’ from Mexico’s Oaxaca State. The name is coined from two words: ‘Bebé’, the Spanish word for baby, and Editora, which means ‘female publisher’ or ‘publishing house’. Their booth featured objects shaped like pillows. In fact, they were both pillows for babies and reading materials designed for falling asleep. Bebëditora’s director comes from the Zapotec, an ancient ethnic group in Oaxaca. Zapotecan languages encompass nearly a hundred dialects and, like Chinese Mandarin, use four tones. Today, the number of Zapotec language speakers has radically decreased, and the director herself has adopted Spanish as her mother tongue. This reality has made her even more determined to preserve and inherit the Zapotecan languages through her own method. The pillows on display were embroidered with Zapotecan words for plants of special cultural significance to local communities, with tags below showing their Spanish translation. Pillow makers used traditional Oaxacan dyeing techniques and hand-sewed the pillows with cotton cloth. I had never encountered a way to protect a language so delicately yet so firmly; it was as if they were enveloping the language in children’s dreams. Vegetal imagery would accompany them as they fall asleep, taking roots in the gentlest manner, unnoticed by all.

The Small Pillow Book, by Bebëditora. Image courtesy of te editions

I would like to conclude this journal with a book I discovered out of curiosity at the booth of Biblioteca Tlacuilo[3], a private library by artist Pedro Reyes rather than a government-funded institute. They placed a metal bookshelf at the rear of the art book fair, filling it with Spanish books and inviting visitors to browse or borrow freely. Although I could only get a very limited understanding of the contents, the library’s open access to the public felt powerful and drew me in.

Tacuilo Library, Pedro Reyes’ Studio. Image courtesy of te editions

A staff member told us Pedro Reyes opened this reading space in the south of Mexico City to the public during the COVID-19 pandemic. Citizens could make reservations to borrow books. When humans were forced into isolation, a library unexpectedly became the medium to connect communities offline and in-person. Pedro’s studio and apartment are also located in this Fauvist building, a home to his book collection and gifted books received from others over the years. ‘There aren’t many libraries in Mexico City, and many university libraries don’t permit borrowing books out’. The staff carried on, ‘We will continue to expand our effort.’ I randomly picked up a small book with an irregular design, and it turned out to be a limited edition of Francis Alÿs’ artist book. It registers his renowned artwork Tornado. I still remember the video of him dashing into a small tornado in a Mexican field, with a camera in his hand, all by himself. Its chaotic visual language is a poignant response to Mexico's contemporary political context. After this trip, I have come to slowly understand the corporeal agency of using one’s own body to confront destruction, disturbance, and turmoil – no matter how many times I watch it, this gesture always remains touching and empowering.

Tornado, Artist Book by Francis Alÿs. Image courtesy of te editions

[1] Fotobook DUMMIES Day, Tropical Reading: Photobook and Self-Publishing, 2nd ed., eds. Jhen Chen, Joanna Lee, K. Chen, Simon Scott, and Valentin Marmonier (Limestone Books, 2024).

[2] Zhang Guangyu, Yuncai (Clouds), 1942.

[3] Tlacuilo: From the Nahuatl language, meaning “painter-scribe” or “pictorial writer.” In Aztec culture, the tlacuilos were responsible for recording history, religion, and daily life through pictographic writing and painting, serving both as artists and as keepers of knowledge.