Three Questions2025 Curatorial FellowSharon X. Liu

A few months into her Curatorial Fellowship at SculptureCenter New York, Sharon X. Liu shares with us how shifting experiences of mobility have shaped her curatorial interests and how she approaches translation as a method for navigating languages, contexts, and publics.

Asymmetry: You’ve navigated a fascinating trajectory, from Hangzhou to Japan, then to Amherst, and now New York. We are curious how this transnational, cross-continental journey has shaped you, both personally and professionally. How do these movements between contexts find their way into your practice, or inform the way you think and work?

Sharon: When I first studied abroad in the 2010s, there was still a sense of optimism about crossing borders. However, after 2020, as that optimism waned, I became more attuned to how differently people experienced international mobility. I waited over a year before Japan reopened its borders to international students. These disruptions to mobility influenced both my personal life and my curatorial interests: I became less drawn to global synchronicities and more to asymmetries within smaller regions. I also began to notice gaps in knowledge about inter-Asian connections that often stay unnoticed within Anglocentric art and cultural scenes.

When mobility slowed down, what I had experienced as personal anxiety about not fitting in has gradually transformed. The feeling of never quite knowing a place well enough to become ‘local’ somewhere has paradoxically made certain connections more visible. I now find myself based in one place while holding a few threads that connect me to a constellation of relationships elsewhere. As a node within this network, I realised one of the things I can do is to activate dialogue between different points.

Sharon in Yamaguchi during Andrew Maerkle's class trip to YCAM OpenLab 2022, organised by YCAM curator Leonhard Bartolomeus. Photo by Hanna Hirakaw

Asymmetry: Translation runs through your practice, both as a method and a metaphor. Using Project Lingxi as a point of reference, how do you understand your role as a curator and researcher who is constantly translating between languages, contexts, and publics? And how do you see this curatorial translation differing from linguistic translation in a more literal sense?

Sharon: Having recently completed an exhibition with Project Lingxi, an independent initiative to develop writing and exhibition projects centred on art and translation in and across Asia, I've come to see myself as someone who wanders alongside artists into what Emily Apter calls the translation ‘contact zone’: not a space of transparent mediation between two languages, but a conflict zone where they collide and mix (Apter, 2006).

To me, curators should make space for artists and their work to arrive on their own terms, in their own time. They should preserve what remains untranslatable when artists’ concepts are rendered into the visual language of an exhibition, and allow the traces of those negotiations within this conflict zone to surface. In doing so, they step aside from familiarity and insipidness and lean into strangeness.

In all translations, what is omitted or misread often becomes the entry points for understanding. Curatorial translation works in very much the same way. Compared to linguistic translation, it involves encounters across space, time, and bodies. It is about the exploration of perceptual ‘inequivalence’ that allows and embraces confusion, futility and struggle.

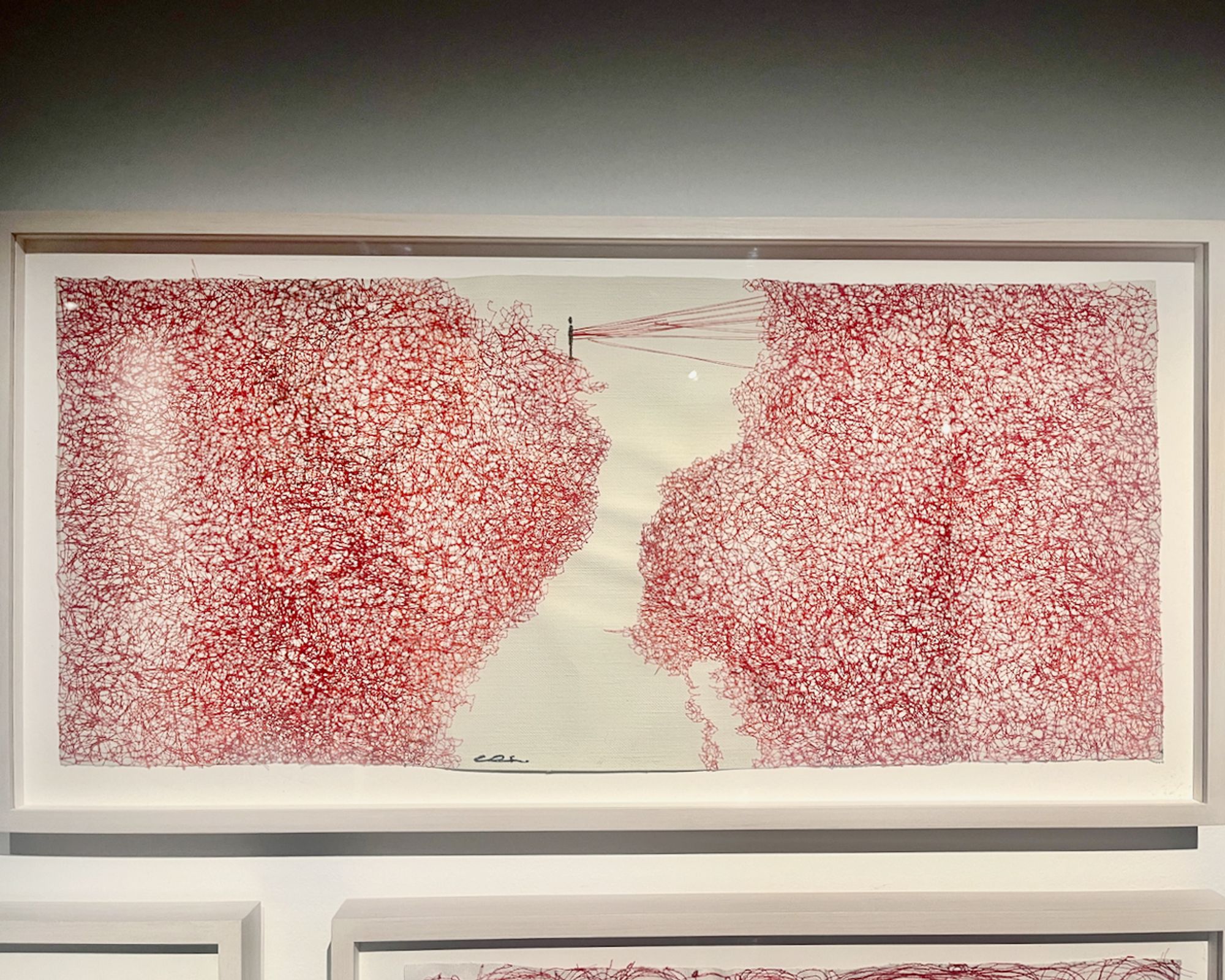

Chiharu Shiota, Connected to the Universe, 2025. Thread and ink on canvas. Photo by Sharon X. Liu during the exhibition ‘Chiharu Shiota–Two Home Countries’ at Japan Society (New York)

Asymmetry: To expand on this idea of ‘translation as action’ in your work, you often engage with archival, historical, and personal materials, sources that are intricate and sensitive, especially in diasporic contexts. How do you navigate these layers of meaning and responsibility when working with such materials?

Sharon: Lu Xun wrote in the ‘New Preface’ to Collection of Stories from Abroad (1920) that during his time studying in Japan, he and his peers harboured ‘a vague and distant hope: that literature and art might transform temperament and even remake society.’ In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Chinese intellectuals saw translation, mostly literary translation, as a vehicle for propagating new thoughts and new structures of feeling, in order to counter a collective sense of indifference.

To me, ‘translation as action’ retains this same urgency today, though we now face a different kind of challenge. Translation itself is changing: what once moved primarily between languages now moves across media and bodies. AI-generated content and algorithmic mediation also make cross-cultural and cross-media transfer far easier, yet this very ease risks flattening how we think and make meaning. This makes it all the more important to ask: when we translate, curate, or create, what drives our work? What makes us human now?

Historical consciousness becomes a kind of calibrating device for the translation process – one that carries ethical implications. I'm drawn to those who think historically, particularly artists who see the present as continuous with the past, and the past as directive for the future. In artworks, historical consciousness shouldn't operate as didactic clarity, but as something open and exploratory, allowing visitors to enter the contact zones where past and present collide.

Sharon at SculptureCenter, New York, October 2025. Photo by Olivia Harrison